- Home

- Resource Center

- Articles & Videos

- The State of Audio-Visual Accessibility and Localization

12 March 2024

The State of Audio-Visual Accessibility and Localization

Let’s look into our crystal balls and consider where we are and the direction we are moving in when it comes to making audio-visual content more accessible, whether that accessibility has to do with language, environmental, and physical restrictions such as deafness or blindness.

The market for captions and subtitles is booming. According to a segment on mainstream TV recently more than 50% of US households watch videos with captions turned on.

Historically, there has been a geographic split between countries that tend towards captions, e.g., Scandinavia, China, and South Korea, and those who prefer dubbing, e.g., Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. In some Eastern European countries e.g., Poland, they have traditionally used the lector style of voice over where one voice narrates all of the parts. This split is changing as technology and other factors make all styles of translation available.

Also, let’s assume that the answer isn’t simply Artificial Intelligence and aim for a slightly more nuanced answer.

Comments About Video

The first thing to state is that not all videos are created equal. They can range from the video of your kid’s solo in the school play to a Hollywood feature film. Their costs can vary from 0 to $1M, and this, of course, will impact the amount that their creators can and will pay to make them accessible.

Here is a selection of video types and their average costs to make. They are estimates, and I am sure you can find solutions for significantly more and significantly less. The price includes all the costs for making the video/film, e.g., planning, script creation, crew, casting, storyboard, production location and equipment, and post-production.

This video will give you some idea of the differences in production quality.

Video statistics

Audio-Visual translation is the fastest growing section of the language industry. There are many websites that extol the virtues of video as a story telling and marketing platform and I have reproduced some of the statistics below.

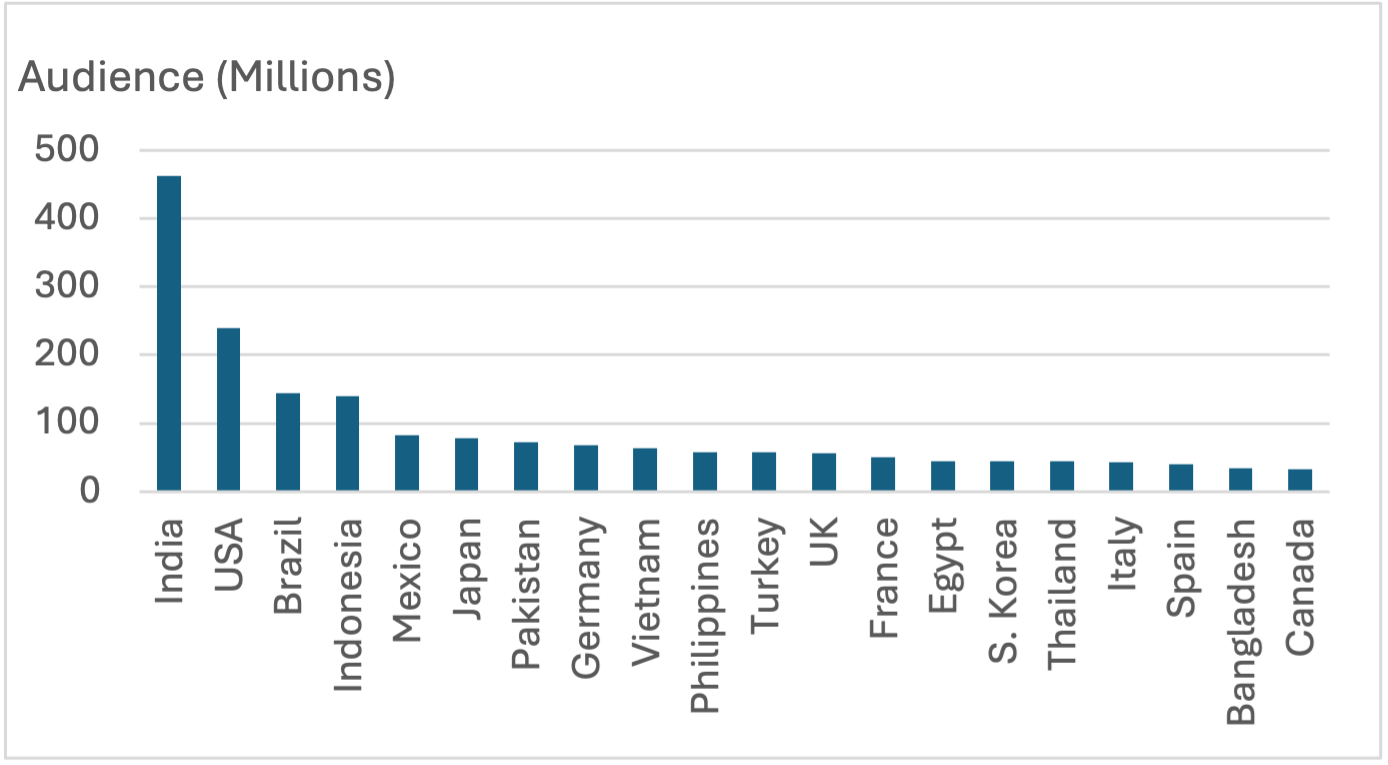

Video is an international phenomenon. YouTube, the most popular video platform, is consumed around the world.

Fig. 1 YouTube Audience

1. 96% of people turn to videos to learn about a product or service

2. 71% of B2B marketers and 66% of B2C marketers use video marketing

3. Having a video on your Website landing page increases conversions by at least 80%.

4. Instagram stories has more than 500 million active monthly users

5. 35% of the most viewed Instagram Stories are from businesses.

6. Video streaming accounts for more than 90% of global internet traffic.

7. 88% of marketers agree that video has improved their ROI

8. Many, many more statistics

Audio Visual Localization up to the End of 2023

Let’s start with some loose definitions. Captions are the display of the text version of speech within a video, and subtitles are the translation of the text display of a video’s dialogue into another language. They are, however, often used interchangeably. The individual timed segments within captioned assets are called cues.

Initially, captioners and AV translators would simply watch the video in one window and produce the captions manually in a text editor. This was a good start but obviously error-prone, with large video files and their associated caption files being sent via email/shared file systems and FTP, and no rigorous enforcement of caption formats during creation. Desktop standalone tools soon came along to make the process of subtitling easier, but the problem of sending all of a project's parts around the world still persisted.

One of the first major steps forward was when cloud-based Video Translation Management Systems (VTMS) arrived on the scene. The customer would upload their videos into the VTMS, and then the linguists would use a browser to watch the video and transcribe, time and segment the video in the source language. Linguists have their own styles. Some would transcribe with a very rough segmentation & timing and then go back to complete the captions. Some would time the captions first and then, in the second pass would transcribe and segment the captions. Some would do all three parts at the same time. It just depended on what they would feel comfortable with.

If translations were needed, the linguist would use the already-created captions, timing, and segmentation, known as a template, and translate what was in the captions, perhaps cue by cue or perhaps taking the cues around the one in question to get some context in the translation and make sure that languages with different structures than the source would be translated reasonably.

Customers required several subtitle specifications such as maximum line length, maximum reading speed, and many formats of subtitle files. Many of these were because of the requirements of television and were carried over into the world of internet video captioning. Now the primary formats for captions are srt, the simplest, and XML-based formats VTT and TTML, specified by W3C. Most of the more successful VTMS systems had subtitle specifications built-in, so the system would warn you if the limits were exceeded and also have the ability to export captions into the most popular formats.

The next important thing to happen to AVT was the arrival of Speech To Text (STT), also known as Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR). This was important because laws in the US and elsewhere were being passed that demanded accessibility for things like educational content so that deaf and hard-of-hearing students could fully participate in lectures, resulting in a considerable amount of content being captioned. There were companies that provided the basic tools, e.g., Google, Amazon, and Microsoft, which, if you used them, would provide a time for the beginning of each word. What you did with that information was up to you. Some companies provide the full caption files, e.g., Verbit, 3Play. These companies would provide different quality captions for different prices.

If you also want these videos translated, it is important that these caption files are as close to 100% correct as possible. So the ASR output had to be reviewed, or post-edited, often quite significantly, which brought the price and the Turnaround Time (TAT) back up to that of human captioners.

While this was happening, Machine Translation, which had been used for text translation for some time, had evolved into Neural MT, which was giving much better results especially when not trained for a specific piece of work. The holy grail of AVT was a fully automated workflow where the video is fed in at one end, ASR and MT do their thing, and the captions and translated subtitles appear as if by magic.

MT in text translation uses the whole text, so the context is available. This is very difficult in AVT, as the source is a series of timed cues. To create the full text, the timing must be removed and then reapplied once the translation has been done. This is difficult because of the structural differences between languages.

Another shortcoming of the traditional approach to AVT is the pivot language approach, which involves using a third language, usually English, French, Russian, or Arabic, but can be any language, as a “bridge” between two languages. This increases the TAT and cost while potentially reducing the quality of the final translation.

We have been in this space for a couple of years and are comfortable, although clients are looking at the text side of the house and are seeing prices drop because of machine-based ASR and MT.

Another innovation was the arrival of Synthetic Voice Overs. This allowed the use of timed text files to create voices in different languages without the need for human voice actors. Again, this can significantly reduce the TAT and the price. The issues for the first round of SVO are primarily in two areas: the comparative speeds of the source and the target languages (how many words it takes to say the same thing and the number of words per minute that native speakers use) and the inability for the SVO voices to create the emotions needed to create the correct tone in all but the most monotonal pieces.

Where we are going – 2024/5

At the beginning of this piece, I said I wouldn’t say the solution to this problem was AI. However, AI has provided tools that have allowed companies to overcome many of the issues mentioned in the previous section.

Large Language Models have made the transcription in speech recognition applications much more accurate.

Natural Language Processing, has been around for a while now, but the technology is rapidly advancing thanks to an increased interest in human-to-machine communications, plus an availability of big data, powerful computing and enhanced algorithms. NLP makes it possible for computers to read text, interpret it, measure sentiment and determine which parts are important. It gives us the ability to understand the text and to make sure that the words that need to be together are together and that the rules of captioning can be implemented.

Machine Translation where advanced AI technology allows greatly improved translation accuracy.

Neural Voice Over Technology where voices are very lifelike and the prosody, the patterns of stress and intonation in speech, can be modified to make a much more convincing voice over.

So when you put all the pieces together, you can do things that weren’t possible even a year ago.

In our case at Fluen, we can provide captions and subtitles at a very high quality in all three parts – transcription, timing, and segmentation and then translate them by using similar technology to the captions, removing the need for templates. Our secret sauce ensures that the translation is as natural as the source and removes the need for pivot languages, as we can easily translate from and to any language. When you look at our captions and translations, there may be a different number of cues in the source and target but they will be natural sounding.

In addition, we can tell if the reading speed is too high and get the AI to paraphrase the segment while maintaining the sense, so the SVO generated will not suffer from the speed problem.

Recently, Slator published a curated list of 50 AI companies in the Language space that had been founded in the last 50 months.

There were 8 categories:

1) AI Multilingual Video & Audio

2) AI Multilingual Content

3) AI Real-Time Speech Translation

4) AI Transcription

5) Workflow Optimization

6) AI Integration

7) AI Models

8) Data for AI

There were more companies specializing in creating Synthetic Voiceovers than any other subtype.

The holy grail of fully automated subtitle generation is not far away for some types of video content.

And then…….

This is a rapidly changing market niche and the speed at which technology evolves is truly astonishing. We will see where we are 12 months from now.

Finally

There are many things that I have left out, including Audio Descriptions and the whole Podcast ecosystem, which can take advantage of much of the technology mentioned above.

It is an exciting area to be part of, and it is also full of potential problem areas, such as the whole deep fake problem. AI-based systems can duplicate likenesses of people saying and doing things they have never said or done. We need to make sure that as an industry we are careful how we apply some of this very powerful technology.

Stay tuned for some truly remarkable innovations in this space.

David Bryant

Dave is the Chief Commercial Officer and Co-Founder of Fluen, an AI-based Audiovisual Translation technology platform that is redefining the conventional wisdom of AVT. Prior to this, Dave was CEO at Dotsub, a pioneer in the AVT services space. He has also worked in sales, software development, and product management in high-tech companies. After visiting many countries for business and pleasure, he became passionate about video and language and their ability to enable knowledge distribution for commercial and social purposes. Dave was born in the UK and attended the University of East Anglia (UEA) where he studied Computer Science and has a management degree from the University of Plymouth. He moved to the USA many years ago and now lives in Brooklyn, NY, with his family